القائمة الرئيسية

Lady Hester Stanhope.... The first women entered Damascus unveiled

الأحد, 22 كانون الثاني 2012 الساعة 09:59 | , Opinions

Jouhina news - Basileus ZENO:

The first women entered Damascus unveiled

Birth: Mar. 12, 1776

Death: Jun. 13, 1839

English Adventuress and traveler, in an age when women were discouraged from doing both. Born in Chevening, England, the eldest child of Charles Stanhope, the 3rd Earl of Stanhope, from whom she inherited both her rare intelligence and her famous eccentricities, and grand-daughter to the Earl of Chatham.

In spite of her upbringing, Lady Hester Stanhope grew to be a brilliant woman, invincibly cheerful and astonishingly independent. By sheer force of character and her skill in so doing attracted the notice of her uncle, William Pitt, a bachelor who needed a hostess in his position as British Prime Minister, and he asked her, In August 1803, to keep house for him. She was then twenty-seven, and in every way a majestic being. She was very tall and well built; her eyes were a greyish-blue, her nose rather large, and her skin almost dead-white. Intellectually, she suffered from impetuosity of temper, and her frequent use of a sharp tongue and nimble wit did not make her beloved as the dispenser of the Prime Minister's official hospitality. She was dazzlingly indiscreet, and Pitt, when questioned as to his attitude towards his niece, said:

"I let her do as she pleases, for if she were resolved to cheat the devil, she could do it."

With Lady Hester at the head of his house and assisting in welcoming guests, she became known for her stately beauty and lively conversation. and when Pitt was out of office she acted as his private secretary.

* Her love…The Hero Of Corunna

Upon his death in 1806, the King awarded her a pension of 1200 pounds a year, in gratitude for her uncle’s service to the country. Pitt had declared before that Lady Hester would never marry, and, indeed, she lived to fulfil his prophecy. The only touch of love romance in her history was the affection she formed for the hero of Corunna, upon whose staff were both her brothers. She was never regularly engaged to him, but there is little doubt that their friendship was great. The last letter Sir John Moore wrote to her before Corunna was: "Farewell, my dear Lady Hester. If I can beat the French, I shall return to you with satisfaction; but if not, it will be better that I shall never quit Spain."

The bringer of the news of Sir John Moore's magnificent retreat across rugged Galicia, and his glorious end on the hills behind Corunna, bore a double load of sorrow to Lady Hester, for in the same battle fell her favorite brother. For a time she was inconsolable, and to her death she treasured some relics of the hero of Corunna - some sleeve-links containing a lock of his hair, and, it was said, a blood-stained glove which he had worn, and upon which she would gaze when she believed herself to be alone.

* Leaving England

* Entry into Damascus

For a while she lived in London, then moved to Wales, where she played at a bucolic existence, she finally became quite intolerant of the restrictions of ordinary society, and determined to travel, and finally leaving England in February 1810, to go on a long sea voyage and never again saw her native land. With her was her physician and later biographer, Dr. Charles Meryon, and a young man named Michael Bruce, who became her lover.

Travel in those days was rather an adventure, and Lady Hester started with a suite which grew as she travelled east. Her brother, who was on his way to rejoin his regiment, accompanied her as far as Gibraltar. She did not stay long there.

The beauties of the Rock were for her spoilt utterly by the presence of too much society, and she went on in the Cerberus to Malta, Corinth, and Athens. As they passed the breakwater at the entrance to Piraeus, a man was seen diving into the sea. It proved to be Lord Byron, who afterwards joined the party for a time, when he had to bear a pressing attack from Lady Hester Stanhope on the low idea he possessed of female intellect.

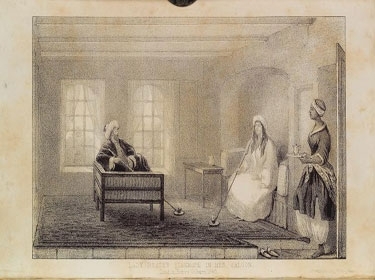

From Athens she moved on to Constantinople, where she at once struck that note of courage and initiative which gained for her the respect and protection of the lawless tribes she afterwards visited. She vowed that, in spite of tradition, she would witness the Sultan's procession to the mosque. She rode to it, side-saddle, and the mere fact that she escaped insult or injury on the day is a good proof of her character. Leaving Constantinople, her party got shipwrecked off Rhodes, and Lady Hester, having lost all of her clothes, joyfully accepted the opportunity of donning male attire. She wore a silk and cotton shirt, striped waistcoat, short cloth jacket without sleeves, and a voluminous pair of breeches, with a sash bristling with pistols and knives, reinforced by a belt for powder and shot. She found some difficulty in arranging her hair under her turban, so eventually she shaved her head and refused to wear a veil. When a British frigate took them to Cairo, she purchased additional male clothing, complete with velvet robe, embroidered trousers, jacket and saber. In this costume, she met the Pasha of Egypt who received her in awe. From Cairo she traveled on to the Middle East, meeting several sheiks in her male clothing.

From Dayr-el-Kamar (in Lebanon) she had written to announce her coming to the Pacha of Damascus, Sayd Suleiman, who had been Sword-bearer to the Sultan Selim, and he had sent one of his pages with a courteous invitation in reply. She was, however, informed that she must wear a veil, as Damascus was one of the most fanatical towns in Turkey (during the ottoman peroide); the scandal of seeing a woman in men's clothes, and unveiled, would be very great, and she would certainly be insulted. But any suggestions as to what she should, or should not, do, invariably roused Lady Hester's opposition. She declared she would enter Damascus in broad daylight, dressed as she was, and unveiled and she did.

On August 27th Lady Hester left Dayr el Kamar, and arrived at Damascus on the 31st of the month.

"I must first mention," she writes to her friend Lord Sligo, "my entry at Damascus, which was one of the most singular and not one of my least exploits, as it was reckoned so dangerous, from the fanaticism of the Turks in that town. However, we made a triumphal entry, and were lodged in what was reckoned a very fine house of the Christian quarter, which I did not at all approve of. I said to the Doctor, ' I must take the bull by the horns and stick myself under the minaret of the Great Mosque.' This was accomplished, and we found ourselves, for three months, in the most distinguished part of the Turkish quarter. I went out in a variety of dresses every day, to the great astonishment of the Turks; but no harm happened.

A visit to the Pacha on the night of the Ramazan was magnificent indeed. Two thousand attendants and guards lined the staircase, ante-chamber, &c. The streets were all illuminated, and there were festivities at all the coffee houses. The message of invitation was accompanied by two fine Arab horses, one of which I mounted; but I am sorry to say they are both dead of the glanders."

Again, in another letter :

" All I can say about myself sounds like conceit, but others could tell you I am the oracle of the place, and the darling of all the troops, who seem to think I am a deity because I can ride, and because I wear arms ; and the fanatics all bow before me, because the Dervishes think me a wonder, and have given me a piece of Mahomet's tomb ; and I have won the heart of the Pacha by a letter I wrote him from Dayr-el- Kamar. Hope will tell you how I got on upon the coast, and if he could make anything of the Pacha of Acre, his Ministers, or the rest of them, who were all at my feet. I was even admitted into the library of the famous Mosque, and fumbled over the books at pleasure, books that no Christian dare touch or even cast their eyes upon."

Far from being attacked or insulted, she was treated with extraordinary deference. Crowds waited at her door to see her get upon her horse. Coffee was poured out on the road before her as she passed. She was saluted as Meleki (the Queen), and all rose to their feet as she entered the bazar an honour generally accorded only to the Pacha or Mufti. Yet at this very time, no native Christian could venture to leave the quarter assigned to him on horseback, or even show himself on foot in a conspicuous garment or turban, without running a good chance of having his bones broken by some zealous fanatic or other.

Lady Hester's next object was to see Palmyra. She had set her heart upon this expedition, all the more as it was generally pronounced to be impracticable. Three Englishmen only had ever been known to reach the place, and of these one returned stripped to his shirt, though they travelled in the humble guise of pedlars. It was out of the jurisdiction of the Pacha, in the hands of the plundering Bedouins, and twenty leagues of waterless desert had to be crossed to get there…..so how she could manage this impossible dream…..we will see later..

Jouhina news - Basileus ZENO:

The first women entered Damascus unveiled

Birth: Mar. 12, 1776

Death: Jun. 13, 1839

English Adventuress and traveler, in an age when women were discouraged from doing both. Born in Chevening, England, the eldest child of Charles Stanhope, the 3rd Earl of Stanhope, from whom she inherited both her rare intelligence and her famous eccentricities, and grand-daughter to the Earl of Chatham.

In spite of her upbringing, Lady Hester Stanhope grew to be a brilliant woman, invincibly cheerful and astonishingly independent. By sheer force of character and her skill in so doing attracted the notice of her uncle, William Pitt, a bachelor who needed a hostess in his position as British Prime Minister, and he asked her, In August 1803, to keep house for him. She was then twenty-seven, and in every way a majestic being. She was very tall and well built; her eyes were a greyish-blue, her nose rather large, and her skin almost dead-white. Intellectually, she suffered from impetuosity of temper, and her frequent use of a sharp tongue and nimble wit did not make her beloved as the dispenser of the Prime Minister's official hospitality. She was dazzlingly indiscreet, and Pitt, when questioned as to his attitude towards his niece, said:

"I let her do as she pleases, for if she were resolved to cheat the devil, she could do it."

With Lady Hester at the head of his house and assisting in welcoming guests, she became known for her stately beauty and lively conversation. and when Pitt was out of office she acted as his private secretary.

* Her love…The Hero Of Corunna

Upon his death in 1806, the King awarded her a pension of 1200 pounds a year, in gratitude for her uncle’s service to the country. Pitt had declared before that Lady Hester would never marry, and, indeed, she lived to fulfil his prophecy. The only touch of love romance in her history was the affection she formed for the hero of Corunna, upon whose staff were both her brothers. She was never regularly engaged to him, but there is little doubt that their friendship was great. The last letter Sir John Moore wrote to her before Corunna was: "Farewell, my dear Lady Hester. If I can beat the French, I shall return to you with satisfaction; but if not, it will be better that I shall never quit Spain."

The bringer of the news of Sir John Moore's magnificent retreat across rugged Galicia, and his glorious end on the hills behind Corunna, bore a double load of sorrow to Lady Hester, for in the same battle fell her favorite brother. For a time she was inconsolable, and to her death she treasured some relics of the hero of Corunna - some sleeve-links containing a lock of his hair, and, it was said, a blood-stained glove which he had worn, and upon which she would gaze when she believed herself to be alone.

* Leaving England

* Entry into Damascus

For a while she lived in London, then moved to Wales, where she played at a bucolic existence, she finally became quite intolerant of the restrictions of ordinary society, and determined to travel, and finally leaving England in February 1810, to go on a long sea voyage and never again saw her native land. With her was her physician and later biographer, Dr. Charles Meryon, and a young man named Michael Bruce, who became her lover.

Travel in those days was rather an adventure, and Lady Hester started with a suite which grew as she travelled east. Her brother, who was on his way to rejoin his regiment, accompanied her as far as Gibraltar. She did not stay long there.

The beauties of the Rock were for her spoilt utterly by the presence of too much society, and she went on in the Cerberus to Malta, Corinth, and Athens. As they passed the breakwater at the entrance to Piraeus, a man was seen diving into the sea. It proved to be Lord Byron, who afterwards joined the party for a time, when he had to bear a pressing attack from Lady Hester Stanhope on the low idea he possessed of female intellect.

From Athens she moved on to Constantinople, where she at once struck that note of courage and initiative which gained for her the respect and protection of the lawless tribes she afterwards visited. She vowed that, in spite of tradition, she would witness the Sultan's procession to the mosque. She rode to it, side-saddle, and the mere fact that she escaped insult or injury on the day is a good proof of her character. Leaving Constantinople, her party got shipwrecked off Rhodes, and Lady Hester, having lost all of her clothes, joyfully accepted the opportunity of donning male attire. She wore a silk and cotton shirt, striped waistcoat, short cloth jacket without sleeves, and a voluminous pair of breeches, with a sash bristling with pistols and knives, reinforced by a belt for powder and shot. She found some difficulty in arranging her hair under her turban, so eventually she shaved her head and refused to wear a veil. When a British frigate took them to Cairo, she purchased additional male clothing, complete with velvet robe, embroidered trousers, jacket and saber. In this costume, she met the Pasha of Egypt who received her in awe. From Cairo she traveled on to the Middle East, meeting several sheiks in her male clothing.

From Dayr-el-Kamar (in Lebanon) she had written to announce her coming to the Pacha of Damascus, Sayd Suleiman, who had been Sword-bearer to the Sultan Selim, and he had sent one of his pages with a courteous invitation in reply. She was, however, informed that she must wear a veil, as Damascus was one of the most fanatical towns in Turkey (during the ottoman peroide); the scandal of seeing a woman in men's clothes, and unveiled, would be very great, and she would certainly be insulted. But any suggestions as to what she should, or should not, do, invariably roused Lady Hester's opposition. She declared she would enter Damascus in broad daylight, dressed as she was, and unveiled and she did.

On August 27th Lady Hester left Dayr el Kamar, and arrived at Damascus on the 31st of the month.

"I must first mention," she writes to her friend Lord Sligo, "my entry at Damascus, which was one of the most singular and not one of my least exploits, as it was reckoned so dangerous, from the fanaticism of the Turks in that town. However, we made a triumphal entry, and were lodged in what was reckoned a very fine house of the Christian quarter, which I did not at all approve of. I said to the Doctor, ' I must take the bull by the horns and stick myself under the minaret of the Great Mosque.' This was accomplished, and we found ourselves, for three months, in the most distinguished part of the Turkish quarter. I went out in a variety of dresses every day, to the great astonishment of the Turks; but no harm happened.

A visit to the Pacha on the night of the Ramazan was magnificent indeed. Two thousand attendants and guards lined the staircase, ante-chamber, &c. The streets were all illuminated, and there were festivities at all the coffee houses. The message of invitation was accompanied by two fine Arab horses, one of which I mounted; but I am sorry to say they are both dead of the glanders."

Again, in another letter :

" All I can say about myself sounds like conceit, but others could tell you I am the oracle of the place, and the darling of all the troops, who seem to think I am a deity because I can ride, and because I wear arms ; and the fanatics all bow before me, because the Dervishes think me a wonder, and have given me a piece of Mahomet's tomb ; and I have won the heart of the Pacha by a letter I wrote him from Dayr-el- Kamar. Hope will tell you how I got on upon the coast, and if he could make anything of the Pacha of Acre, his Ministers, or the rest of them, who were all at my feet. I was even admitted into the library of the famous Mosque, and fumbled over the books at pleasure, books that no Christian dare touch or even cast their eyes upon."

Far from being attacked or insulted, she was treated with extraordinary deference. Crowds waited at her door to see her get upon her horse. Coffee was poured out on the road before her as she passed. She was saluted as Meleki (the Queen), and all rose to their feet as she entered the bazar an honour generally accorded only to the Pacha or Mufti. Yet at this very time, no native Christian could venture to leave the quarter assigned to him on horseback, or even show himself on foot in a conspicuous garment or turban, without running a good chance of having his bones broken by some zealous fanatic or other.

Lady Hester's next object was to see Palmyra. She had set her heart upon this expedition, all the more as it was generally pronounced to be impracticable. Three Englishmen only had ever been known to reach the place, and of these one returned stripped to his shirt, though they travelled in the humble guise of pedlars. It was out of the jurisdiction of the Pacha, in the hands of the plundering Bedouins, and twenty leagues of waterless desert had to be crossed to get there…..so how she could manage this impossible dream…..we will see later..

اقرأ المزيد...

Pal. Sisters as Keepers of their Brothers inside Emergency Damascene Shelters

Pal. Sisters as Keepers of their Brothers inside Emergency Damascene Shelters  White House Expected to Ease Sanctions Targeting Syria …Iran to Follow?

White House Expected to Ease Sanctions Targeting Syria …Iran to Follow?  Popular Demands Transmogrified to Achieve What America’s Might Failed to *.

Popular Demands Transmogrified to Achieve What America’s Might Failed to *.  Un-evenhandedness the core of all evils

Un-evenhandedness the core of all evils  Superstitious Obsession

Superstitious Obsession  ?Do you believe in Astrology

?Do you believe in Astrology  living the ultimate freedom

living the ultimate freedom  Birth control and how do parents perceive it

Birth control and how do parents perceive it  الرئيس الشرع: الحقوق الكردية مصانة بالدستور ووحدة سوريا وسيادة القانون أساس الاستقرار والتنمية

الرئيس الشرع: الحقوق الكردية مصانة بالدستور ووحدة سوريا وسيادة القانون أساس الاستقرار والتنمية

منتخب مصر يخرج على يد السنغال من منافسات كأس إفريقيا 2025

منتخب مصر يخرج على يد السنغال من منافسات كأس إفريقيا 2025

نيويورك تايمز: الهجوم الأميركي على إيران بات وشيكاً

نيويورك تايمز: الهجوم الأميركي على إيران بات وشيكاً

مسيرات “البيرقدار” التركية تستهدف ريف حلب الشرقي

مسيرات “البيرقدار” التركية تستهدف ريف حلب الشرقي

الشيخ الهجري : إسرائيل أنقذتنا من الإبادة والعلاقة معها تاريخية وطبيعية

الشيخ الهجري : إسرائيل أنقذتنا من الإبادة والعلاقة معها تاريخية وطبيعية

"معاريف" الإسرائيلية: تفعيل التشويش على نظام تحديد المواقع العالمي (GPS) في أجزاء من العراق وإيران

"معاريف" الإسرائيلية: تفعيل التشويش على نظام تحديد المواقع العالمي (GPS) في أجزاء من العراق وإيران

الذهب يقترب من ذروته التاريخية والفضة تتجاوز 90 دولاراً لأول مرة

الذهب يقترب من ذروته التاريخية والفضة تتجاوز 90 دولاراً لأول مرة

وزارة الإعلام تحتفظ بحق بث لقاء الرئيس الشرع مع قناة شمس عبر منصاتها الرسمية

وزارة الإعلام تحتفظ بحق بث لقاء الرئيس الشرع مع قناة شمس عبر منصاتها الرسمية